Clipse: When The Last Time You Heard It Like This? (Part 1/2)

In the first instalment of a two-part interview, Pusha T & Malice reflect on the long path to their artistic reunion, and the process of making their first album in fifteen years.

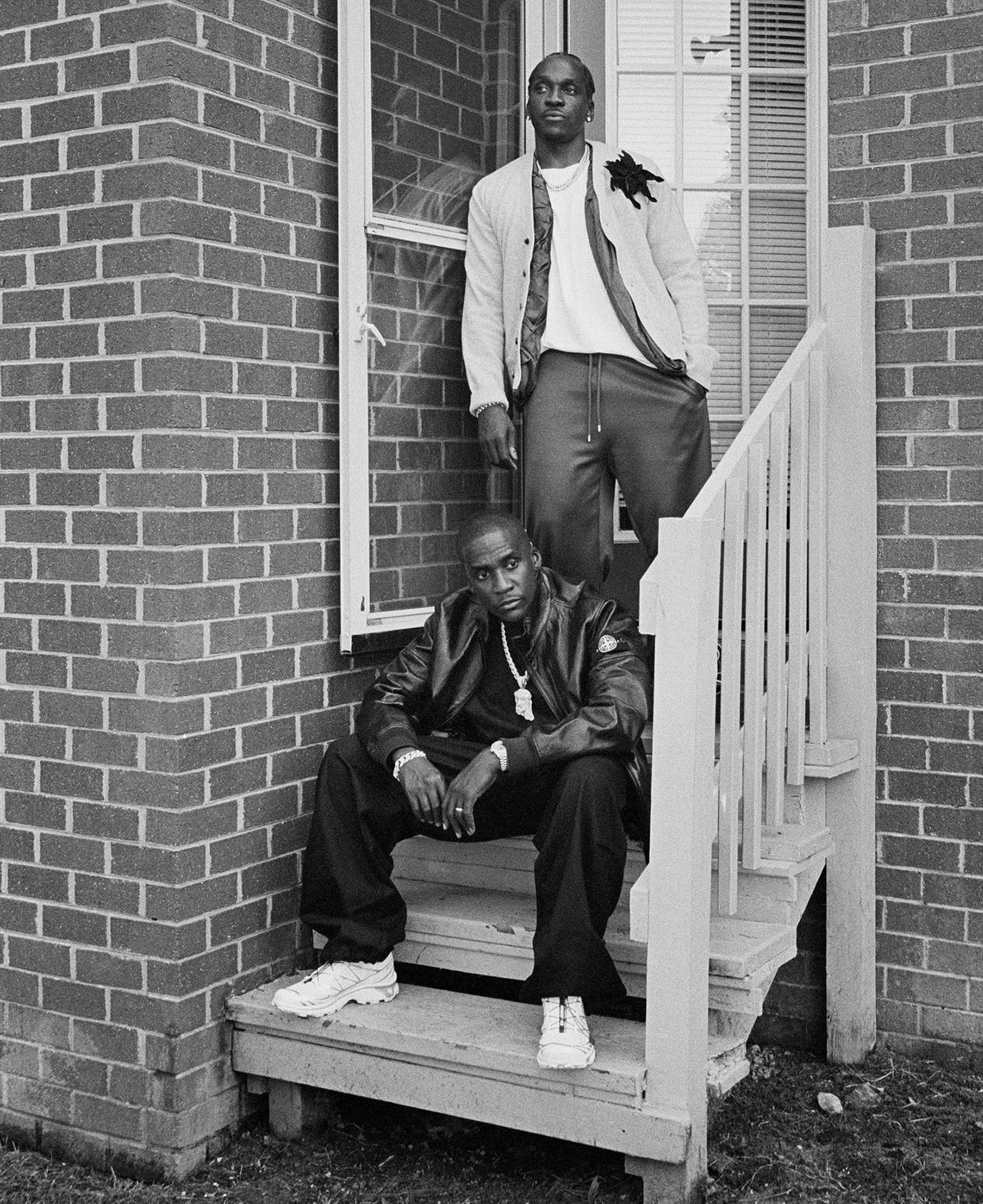

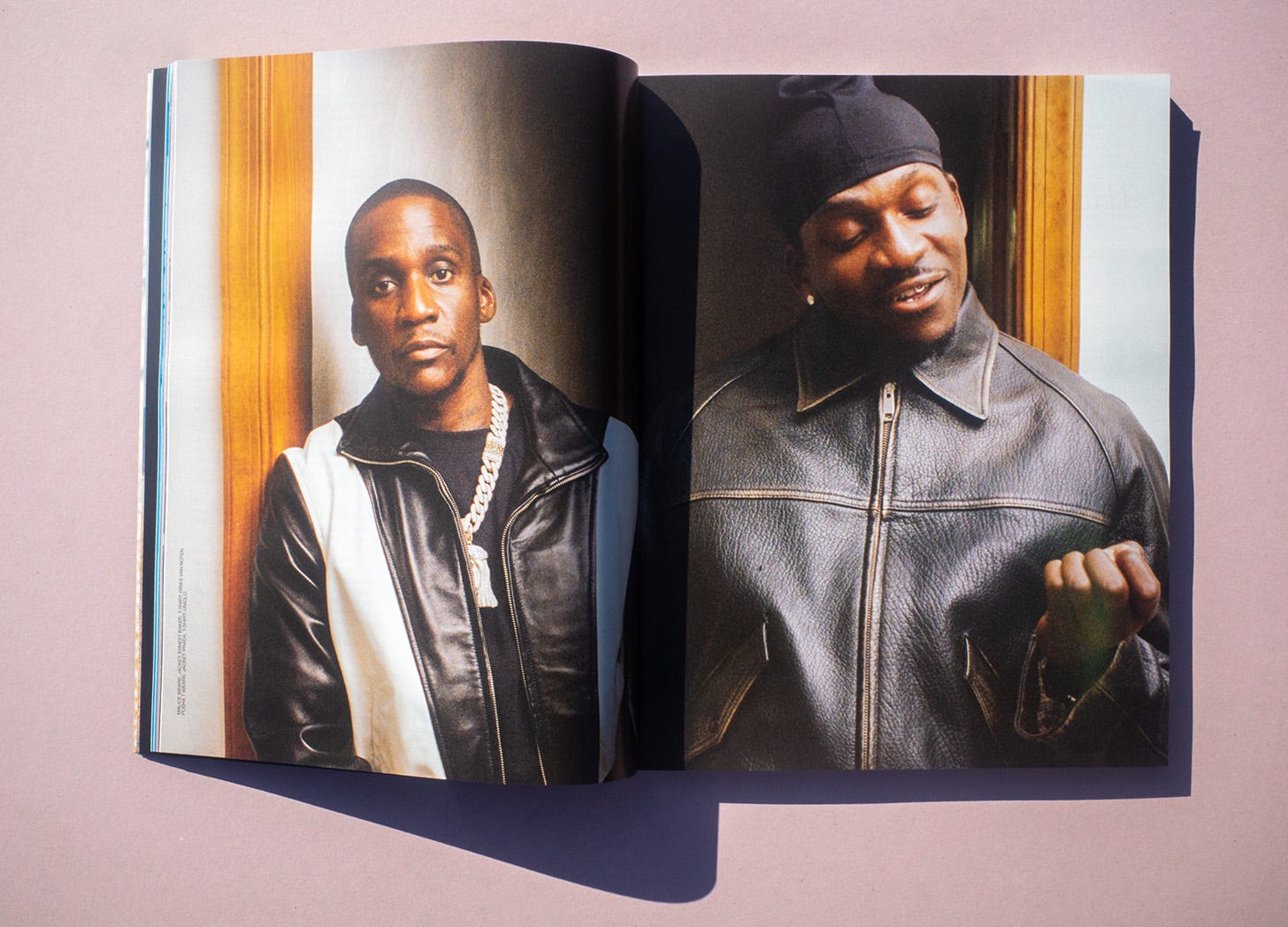

Photography by Rahim Fortune

Words by Mardean Isaac

Fashion by Marcus Paul

One evening in June, 2023, the Clipse strode across the Pont Neuf—the oldest bridge in Paris—between seated rows of illustrious guests. Malice (Gene Thornton, b. 1972) and Pusha T (Terrence Thornton, b. 1977) were modelling at their old friend Pharrell Williams’ first show as creative director of Louis Vuitton. Wearing a knee length coat and varsity jacket emblazoned with glaring oversized graphics, they stared eerily into the distance. Violet streaks were still visible in the sky above the dark blue Seine; a grid of powerful lights beamed across the Damier pattern of the runway, casting long shadows behind the various walkers. Among the medley of strings, pianos, and gospel music accompanying them, a new, unreleased song played out. “Beat the system with chains and whips,” Pusha incanted on the hook, double entendres flipping bondage into liberation through the ownership of jewellery and plush automobiles.

“Chains and Whips” ended up as one of twelve tracks on Let God Sort ’Em Out, the first Clipse album in 15 years, entirely produced by Pharrell. Recorded between Paris and the trio’s hometown of Virginia, the record represents a return to old ways as much as a new beginning.

It was Pharrell who first envisioned the brothers forming a group. Steeped in music from childhood, he met Malice on the Virginia oceanfront in 1990, where youngsters gathered to freestyle. At that stage, Malice was already rapping—and instructing his little brother on distinctions in matters of taste. At a session with Pharrell and former partner Chad Hugo, Pusha—whose rap alias was also given to him by Pharrell—wrote his first verse. The producer came up with the group’s name—playing off the overlapping motion of the celestial eclipse—and secured their first record deal.

The early years of Pharrell and Hugo’s collaboration as The Neptunes were marked by hyper-productive genre-crossing sessions in Virginia Beach, which yielded hits for hip-hop, R&B and pop artists. Clipse secured their share of that glut of beats for Lord Willin’ (2002). Spurred by percussive single “Grindin’”, the group began—in their own telling—to play “brown bag shows” to local hustlers; but with their next album, their audience soon extended to white college kids they called “clipsters”.

Hell Hath No Fury (2006), another Neptunes production, is one of the most disquieting and artistically singular explorations of criminality in the hip-hop canon. The brothers quested with fervour for the outermost limits of both the seductions and horror of avarice and violence. Their lapidary bars channelled the mystique of the outlaw vernacular and the thunderous register of scripture. Endless distillation of street realities became a way of refining the truth of the world beyond the street.

Then everything fell the fuck apart. In 2010, a cluster of drug conspiracy sentences saw nine of the Clipse’s closest associates incarcerated in long bids, including their former manager Anthony Gonzalez. Chilling prophecies of downfall on tracks like “Nightmares” had come to pass.

The brothers remained free. But the Clipse itself became a casualty of the events. On a flight out of Virginia, Malice announced to his brother he wanted out of the group.

The parting of ways felt like a chapter in the saga of their artistic personas as much as an event affecting the human beings behind them. Pusha’s flamboyant recklessness dictated persevering; Malice, deeply shaken by not only the imprisonments but the vision of his music as a soundtrack to wrongdoing, succumbed to his fearful prudence. Pusha pursued a solo career in accordance with his brazen sensibility (“You think Tony in that cell would have made us timid? / we found his old cell, bitch: we searchin’ through the digits”, he rapped on “40 Acres”); Malice was possessed by a religious revelation, compelling him to turn away from materialism and hedonism and towards God. The brotherly dynamic obtained, even as the musical act did not. There was no beef; no conventional break up. Malice supported Pusha; Pusha respected Malice. The asterisk of the group’s potential return was founded on that bond, and the artistic greatness that only it could unleash.

During their hiatus, it became clear that those who pigeonholed the Clipse as “coke rap”, or encouraged them to dilute, compromise or diversify their approach, turned out to be projecting their own limitations, not exposing those of the music. Instead of Clipse bending to the world, the world bent to them.

The group’s influence could perhaps be felt most prominently in artists who didn’t rap about street shit. Tyler claims to have been permanently transformed by “Mr. Me Too”. Kanye drunkenly ranted about how “everything is Pusha T” and cast Pusha as a protagonist during his most panoramic artistic run. A point shrouded by later events: Drake idolised the Clipse so much that he bought a mic apparently signed by Pusha on eBay and rapped the group’s songs into it in his basement.

Let God Sort ’Em Out is guided by a resolute faith in artistic fundamentals long mastered by its makers. It feels like a continuation of an obsession with craft that is inherently restless and abhors staleness. But the album also registers the passage of time; it is deepened by tragedy, yet freshly enlivened by the prospect of joy in creation.

Some Pharrell staples are at play: tactile drum sounds and patterns, a mastery of synth tones; the album opens with a four count. Striking soundscapes include the escapade patters of “EBITDA”, the stomping, fumy “FICO”, and the hookah-scented “So Be It”. As ever, Clipse hooks rise to the level of Greek choruses, Pharrell’s gospel snark on “So Far Ahead” and purifying witness on “Grace of God” particular highlights.

On a lean album in terms of length as well as instrumental stretches, the beats act as a pedestal for language—and justifiably so. “Lifted all this weight / now I live behind the gate”, Pusha says on “EBITDA”, punning on selling dope as repetitive exercise and a burden to be cast off, the terseness of the couplet enacting the stark simplicity of material aspiration. “See mine made sure he had every base covered / so imagine his pain finding base in the cupboard”, Malice raps on “Birds Don’t Sing”, encapsulating an entire generational crisis in a single moment of domestic drama.

In a world that rewards lies, the Clipse’s devotion to honesty feels almost saintly.

Within about half a minute of the album’s opening track, Pusha yearns for the touch of his deceased mother, mentions his wife’s miscarriage, and the relief that his son—craving siblings—didn’t notice she was pregnant.

“Birds Don’t Sing” is an elegy for the brothers’ parents: their mother passed away in November 2021, and their father the following March. Over a forlorn piano riff, the brothers narrate the moments they discovered those deaths, and evoke the whole course of their family history through those discoveries. Just as they are exposed to the tender fragility that suffused their parents’ final moments, they become stewards of their legacy. The composure of the brothers’ delivery only heightens the pain behind their words, as if they had to maintain the verbal gifts bequeathed by their parents to pay appropriate tribute to them.

The brothers spoke to me from their home state, but in separate spots, over a call: Malice in the same place he’s had for over two decades, Pusha in his mansion on the Lafayette River, a more recent investment. I ask Malice if he’s into interior design like his brother. “Not as much as Pusha is, but I’ve been doing a lot of renovating and decorating; I did the whole house actually,” he replies. When I ask about the physical aspect of the work, he says: “I do nothing myself. Everyone tells me: ‘you can do this yourself’; I’m like, I’m not into none of that: I’m not trying to be frustrated, aggravated or nothing. I’d rather pay for it.”

“I guess the mantra ‘brick by brick’ isn’t necessarily that literal,” I offer. “Not every time,” he responds through laughter.

BRICK: What were the conversations or events that led you guys to start working on the album?

Malice: My reintroduction started with working on the Jesus Is King album with my brother and Kanye, and being able to write on a few songs. That’s when the activity started: back with the brainstorming and coming up with verses, and just me being in that atmosphere again. And I always knew we were always able to do it—it was something that could be done—but that was part of the baby steps that was happening with me, to start interacting with rhyming with my brother again. And then we did “Punch Bowl” on Nigo’s album, and my brother put me on his album It’s Almost Dry with “I Pray for You”, and those songs were well received. It was just the timing: and it was natural, it was organic, and it was just a perfect flow.

BRICK: The album was made in Virginia and Paris. How would you compare your recording set up in each place: the studio itself and the structure of the team?

Pusha T: The recording set up in Paris was pretty unique in the sense that it was done in the Louis Vuitton atelier. There was a room that has all of the music equipment—microphones, laptops, so on and so forth—and at any given time, the studio area could be four or five of us, with the engineer. There’s just a sliding door that can separate you and you’re looking out into the design studio, into a room of 30-40 people. Versus: we’d take some of the ideas home, and we’d record in a private home studio of the first engineer and studio owner that started us out: his name is Rob Ulsh. He basically started the Neptunes, Timbaland, Missy: all of those albums were recorded in his home, and he embraced Teddy Riley when he moved to Virginia as well. So now he works out of his home and only works with certain individuals—and of course we have free range there. It’s in a suburban neighbourhood, just tucked away—you would never know what’s behind those doors.

BRICK: Did you sketch out ideas for the record as a whole or for particular songs before getting started, or were you guided by what spontaneously emerged as you began to work?

Malice: I feel like it’s the same formula that’s ever been with the Clipse: it always starts with that foundation, with the beats. And you find that, from there, that’s where the ideas and the hooks and the background is formed. Once you crack that code, everything opens up.

Pusha T: This album was made with composition in mind, though. Meaning: being extremely mindful of hooks and flows and cadences. They all have a quality: the whole album was about cohesiveness, from themes to the soundbed of it all. There was a super intention behind making it sound cohesive, and making it be cohesive. I’m kinda feeling that a lot of that isn’t out there today. We’re album artists, and I think there was a heavy intention on showcasing that.

BRICK: Malice, when composing your verses for this album, how did you draw on your experiences over the past 15 years?

Malice: I think with the Clipse, that’s all it’s about: staying true to your art, as well as to our real life experiences. With this album, what you’re getting is life, experience, growth, maturity—and just the Clipse in real time. Not patterning ourselves or fashioning ourselves after anything, which we have never done—never chased after anything that was going on. I feel our music is ahead of the curve—and real, and it’s genuine. And that’s one of the things that I think we pride ourselves on. It’s always a look inside our lives, and a look as to what we’ve been through and are going through. It’s just real, in every aspect.

Click here to read Part Two.

This story was originally published in BRICK Edition 12, released in 2025.

Edition 12 also features Navy Blue, Jim Legxacy, Tommy Wright III, DJ Spanish Fly, Nia Smith, JOBA, and many more.

Click here to purchase the issue from our store,

or join our paid tier on Substack to receive a free copy as your welcome gift.

🔥