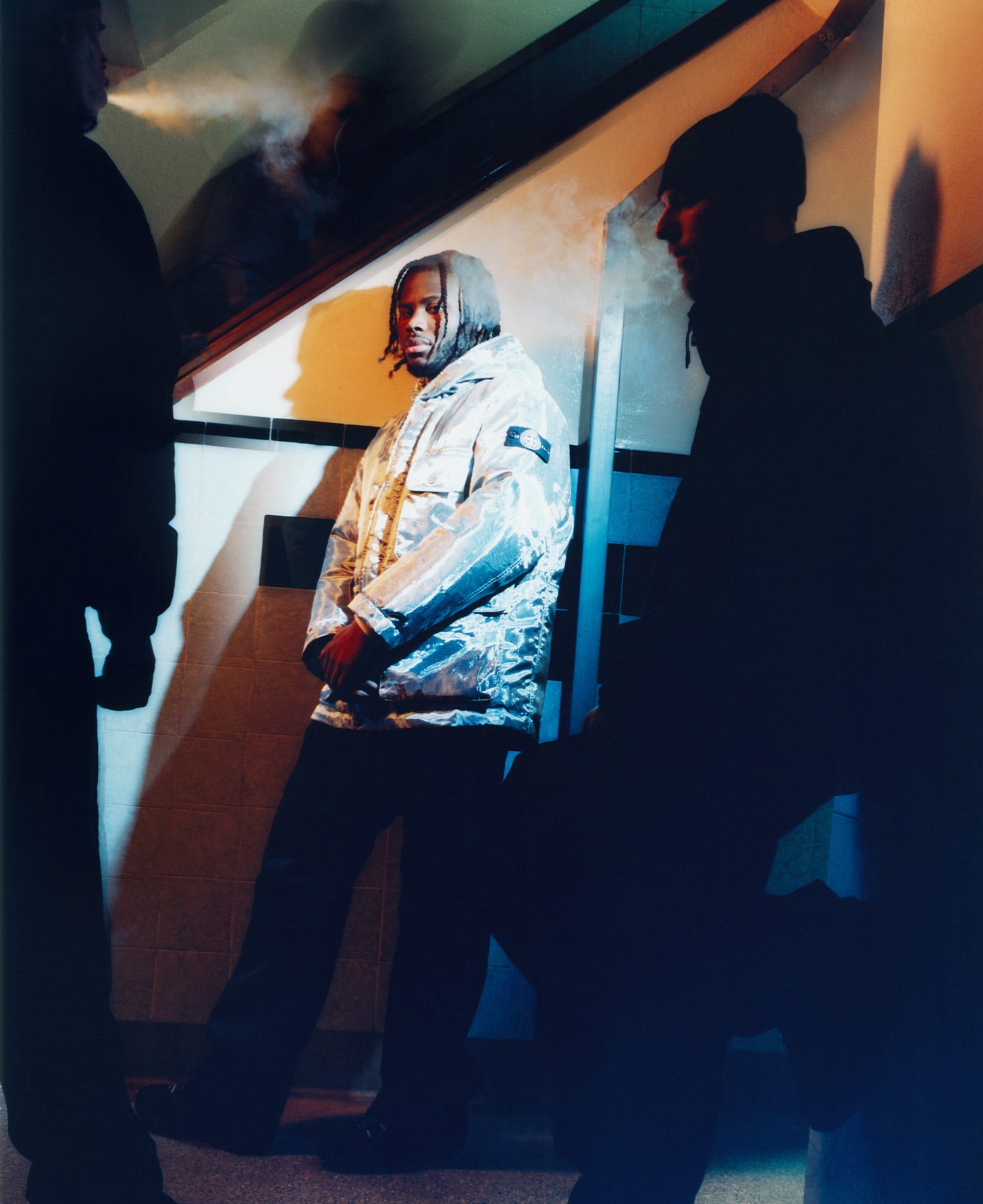

Jim Legxacy: Home Sweet Home

Join us for a family gathering at Jim’s mum’s flat: Settling sibling disputes with FIFA, United vs Spurs on the TV, cups of tea, chin chin, and a chat about making one of the albums of the year.

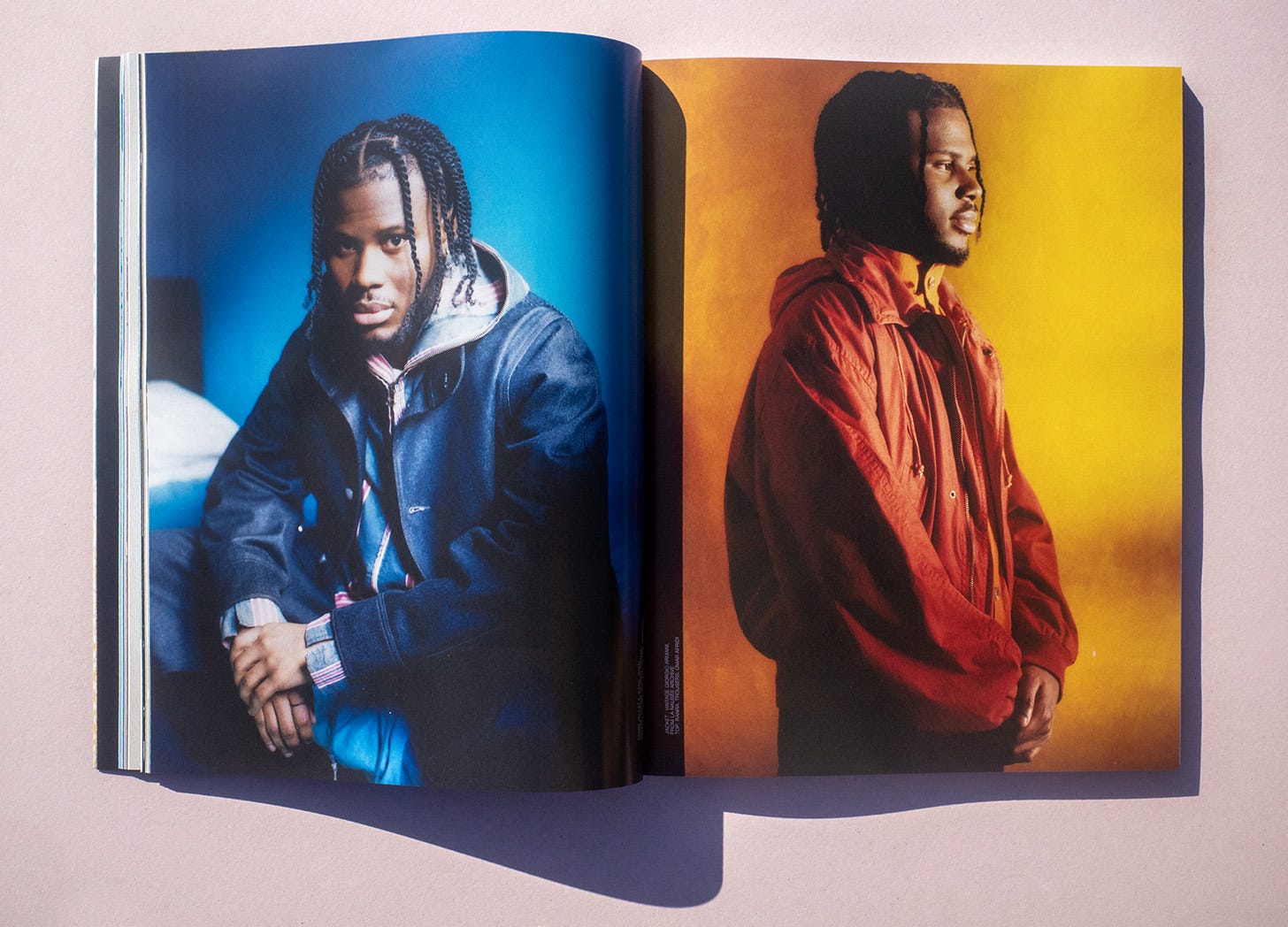

Photography by Theo Cottle

Words by Hayley Louisa Brown

Fashion by Guy Louis Miller

“Come in… if you’re handsome!” calls Mrs. Olaloye, in response to the knock on the front door that she knows her son is responsible for. She pads down the hallway to open up, leaving me in the front room with her youngest son, Ben, who has just returned from playing football and is now frantically turning on Sky Sports to catch what’s left of the Manchester United game.

Jim enters, exclaiming in delight to his mother, before he’s immediately followed inside by many more footsteps. Along with Jim, there’s his manager Luke, plus a handful of close friends. Shoes are removed at the threshold, the entryway looking like a monochromatic stockroom at Nike (all black, all Air Max 97s), and the apartment full of noise. Mrs. Olaloye brings out a bowl of Chin Chin, a Nigerian fried dough snack, and boils the kettle. Our photographer Theo and stylist Guy are in one bedroom, setting up lighting and manoeuvring around pieces of furniture as myriad conversations ebb through the walls.

Jim’s older brother, Ayo, has pulled out a special Assassin’s Creed deck of Magic: The Gathering cards to show Luke, whilst the rest of the boys pile onto sofas to watch Tottenham score their second goal of the game. It’s then that I realise that all 3 of the brothers support different teams.

When, a few weeks later, I reunite with Jim to interview him, it’s one of the first things I ask about. “It’s a mess, bro!” he exclaims, shaking his head before giving a much needed origin story on this Shakespearean family divide:

“Well, my Dad supported Man U, but my [older] brother was like, “I don't really like the colour red.” Those were our priorities when we were kids. I loved red, so I heard Man U and I was like, “hell yeah, that's lit!” But my brother wanted to support a different team. So he’s Arsenal. My sister, when she was alive, me and my little sister were supporting Man U with my Dad. Then, my little brother was born and he was like “I'm not really on this Man U propaganda, I'm not feeling it. He initially thought Liverpool was called Liver-poo, so he would laugh at that all the time and based on that, that’s who he supported. You know what, when you're a kid… your priorities are so dumb. When we play FIFA, it’s beef. I can't lie, there's been times where Liverpool are losing and I'll just be creasing, but now obviously Liverpool are way better than Man U. I don't even come home when they lose.”

This natural flair for storytelling is something that’s reflected in Jim’s music. He refers to it as a “hodgepodge,” which is a humble discredit to the magic that his unique blend of styles conjours. Listening to anything by Jim Legxacy is like that scene in A Clockwork Orange where Alex has his eyes pinned open; each song so layered that a never-ending stream of references flash before you as you listen.

Back at Jim’s own apartment (a short walk from his Mum’s place) his Apple Music playlist streams through the TV. He sings along to every track that appears; we start with Caroline Polacheck (“her Desire, I Want To Turn Into You album is so sick.”) before pivoting to The Sugarcubes, then CATALYSTPVD and YhapoJJ, before a hard left turn into Lady A’s “I Need You Now.”

I wonder what his favourite ever record is, considering the sheer breadth of his tastes? I mentally prepare for a few minutes of umm-ing and err-ing in response, imagining the rolodex of options scanning behind Jim’s eyes. Surprisingly, the response is almost instantaneous:

“The Life of Pablo. That's the first rap album I sat through top to bottom. For that to be my first one is insane because a lot [of albums] have structure and organisation… But the first one that I found was the most chaotic Kanye album ever that had no cohesion, and no real sense of identity outside of the fact that it's chaotic, and I think that has shaped so much of what I do.”

And is his approach to creating his own work chaotic, too?

“It's a bit off the cuff, but I usually start with a four bar loop or an eight bar loop. I write a chorus on that and then leave it for months, because I feel like you have to let your demos age a bit before you understand them. Something like ‘Aggressive,’ that came out almost a year after when it was started. So it just takes a while.”

“Aggressive,” the lead single from his forthcoming mixtape, Black British Music, feels so distinctly familiar from the very first listen; new but nostalgic. Retro-futurism at its finest, with Jim’s sweetly reserved vocals mixing seamlessly with samples ripped from the Grime history books, sandwiched between an audio water-mark for the project, the words “Black British Music” echoing like a pirate radio station; reminding you exactly where you are - as if you could forget.

“I remember when I made the hook, I knew there needed to be a line being repeated, but I didn't know what it was. I was looking through a bunch of British classics and I remember seeing ‘Oopsy Daisy,’ and thinking ‘the “crush” sound could be interesting - just taking the word ‘crush.’ And from that, it started to come together. I felt like it assisted in weaving the narrative together a lot.”

Luke interjects, momentarily stepping in as interviewer:

“Would you say people like Dizzee and Giggs, for you, are like Black British classics?

I smile to myself; I love that, despite knowing Jim inside-out, he’s been listening intently to our conversation and has a genuine curiosity. The pair have known each other only a couple of years, but have a shorthand like they met on the first day of preschool. Jim nods: “Yeah, I think Chipmunk, Giggs, Dizzee, those are the ones that I feel like, in hindsight, were truer artists. I respect what those guys built for themselves, and for us.” Luke speaks up again, finishing up the thought: “Yeah, they’re the people that broke down the doors in the industry, I think, for you guys to exist.” and Jim nods again, with enthusiasm “Massively. So, for me, it's important to reference those guys and give them their props and what they deserve.”

Embedding the artists he admires into his own music acts as a public love letter; Jim really, really loves music. “A few years back I used to dig through SoundCloud all day, dig through YouTube as well, just trying to find music that interested me. But right now, I find it really difficult to find new things; because I feel like everyone's habits for finding music have kind of aligned into one place.” - and though Jim doesn’t say it specifically, he can only be referring to TikTok - “So I guess what I mean is, I find it hard to find something different. I find it easy to find what's popping. It's so easy to find that. But I do feel like what's not popping, that's what I've been looking for.”

I ask when Jim’s deep-rooted love for music turned from appreciation to creation? How did he begin his journey into making music, rather than just soaking it all in?

“Initially I was a big MF Doom fan, a big Kendrick fan, a big Avelino fan as well. So when I first started making music, I wanted to make music like that. I was learning to rap on those classic rap beats, and then I got, in my opinion, pretty good at it… but I felt like the process wasn't stimulating me enough… so I started making my own beats. Every time I learned to make something new, I was like “alright, done with it. Lemme make something else.” I kept doing that until one day I got to a point where I started singing instead of rapping, And I kept moving, acquiring new skills. I was so obsessed with the process. I started listening to more music, gathering more knowledge, and then it just turned into what I do now.”

And what he “does now” is so special and oftentimes, unexpected, that it feels as though it should have always existed. The layers of sounds, samples and fingerpainted strokes of genius give reassuring comfort; moments of vague deja-vu when you hear an 8-bar amongst the noise that shaped your own teenage years. In “Homeless n****a pop music” it’s Dizzee Rascal, Michael Jackson, Sampha. In “candy reign (!)” It's Soul For Real and Tinie Tempah. It is, in its own way, totally anarchic. In Jim’s own words: “bro, I can't lie. I think sometimes I just want to hear the song [I love] in my song.”

In his living room, I ask what instruments he can play, after spotting a keyboard carefully tucked underneath the television. “None, absolutely nothing.” he says, pulling the instrument towards him and revealing the letters A, B, C, D, E, F and G drawn on the keys over and over in Sharpie. I laugh, and he continues “Yeah, I can't play none. I just figure it out… I have a gift for what I think sounds good, and I never doubt that.”

Jim’s use of samples and interpolations act as instruments, adding layers and dimension, responding in the same way an orchestral group would to their conductor telling them to play more loudly or to quieten down. That’s exactly what Jim does: he conducts the samples. He tames them. Bends them. Pulls them out gossamer thin and plucks them. Squashes them into flat little pucks and stacks them. Every combination is a snowflake.

“I feel like that's the thing with samples,” he states. “They can be done so lazily and I really don't want to be like that. I want samples to be tasteful and strong and meaningful. Sometimes I hear the same key [in my music as in a pre-existing song]… and be like, “What does this remind me of?” Do you know what I'm saying? And when I figure out what it reminds me of, I'll drag [the sample] in and it fits perfectly. So sometimes it just feels divine. It feels divinely guided”

From my perspective, the switch from rapping to singing was divinely guided too - he only pivoted during the 2020 pandemic-induced lockdowns: “I think, obviously, lockdown was a terrible time, but a lot of people discovered so much about themselves in that isolation. I felt like I did too.” Jim spent that period of time at his Mum’s spot, no escape from the aforementioned football rivalry (“there was a lot of conflict in the house!”), but despite the close quarters “a lot of it was just me still learning music and teaching myself, trying to get things right. I was locked in, plugged into the matrix.”

I find it hard to imagine the Olaloye house during lockdown, having only seen it full - visitors fighting for sofa space, spreading out into the hall. My lasting memory of my visit was of Mrs. Olaloye, older brother Ayo, and friends Daniel and Ari on the sitting room floor, playing Ludo. The atmosphere reminded me of my own home as a teenager; it was the place my friends would congregate. I ask Jim if his house was like that, too? “Low key!” he exclaims “That’s what is, but also my mum grew up with nine siblings. She grew up in a house with 11 of them in Nigeria with two bedrooms. So my Mum doesn't like being alone. She can't really deal with it. She likes companionship, so when there's bare people in the house she feels very good. She really likes it.” And how does she feel about Jim’s unorthodox career choice?

“She's always been supportive, from when I was a kid. She was just like, “whatever you want to do, make sure you don't give up.” And I feel like those foundations, from such a young age, encouraged me to keep exploring. I think that was so necessary for me to figure out who I was and who I was going to be. So I'm grateful for it. I'm grateful for the whole thing.”

And Jim’s upcoming project, Black British Music, which (not by accident) shares the same acronym as the Blackberry messaging app that reigned supreme before the iPhone, is a culmination of everything he’s learned so far: “I feel like there's a bit of a reset going on within Black British Music right now,” Jim says, explaining “so much music in the last five, seven years was heavily commodified and a lot of artists that were getting traction were trying to make a dime as opposed to communicating who they are and what things mean to them. So with this mixtape. I wanted to communicate narratives and let them be what they are proudly.” he says of the record. And the name? “Patriotism!” he cracks, before clarifying: “Well, only half of it is irony. I grew up in a Nigerian household. When people ask me what country I'm from, I'm always going to say I’m Nigerian. But when I go to Nigeria, they don't refer to me as Nigerian… So I'm not that. I'm something in between my Britishness and my Nigerianness. Do you know what I'm saying? So this mixtape is me being able to sit there and embrace everything; embrace Nigeria, embrace afrobeats, embrace everything that makes me the Nigerian part, but also embrace grime, embrace all the things that make me Black British as well.”

He goes on: “It's confusing, but it's something that we have to start thinking of now, before we try to force things on our kids. My kid's not going to grow up in a Nigerian household. I was raised with the cultural richness that my mum and my dad brought to me [from Nigera], and I'm not going to bring that to my kid. So my kid is actually going to be Black British, one of the first waves of African Black British people. And if I start embracing that now, I'll be able to understand my kids a bit more in the future.”

Jim’s “hodgepodge” approach to music appears to mirror the feelings he shares around his identity, too. He is a self-taught savant; and like an athlete, his PB is never enough. I ask what goals he’s currently working toward, and the answer, it turns out, is a tl;dr of this entire article:

“I just want to grow innit… I just want to execute my vision the way I see it in my head, and I feel like if I do that, I'll be happy. So that's my goal. Bottom line: I’m excited.”

This story was originally published in BRICK Edition 12, released in 2025.

Edition 12 also features Clipse, Navy Blue, Tommy Wright III, DJ Spanish Fly, Nia Smith, JOBA, Young T & Bugsey, and many more.

Click here to purchase the issue from our store,

or join our paid tier on Substack to receive a free copy as your welcome gift.